This is part 1 of 3. Part 2 is here. Part 3 is here.

Coram me tecum eadem haec agere saepe conantem deterruit pudor quidam paene subrusticus, quae nunc expromam absens audacius, epistula enim non erubescit. ardeo cupiditate incredibili neque, ut ego arbitror, reprehendenda, nomen ut nostrum scriptis illustretur et celebretur tuis; quod etsi mihi saepe ostendisti te esse facturum, tamen ignoscas velim huic festinationi meae; genus enim scriptorum tuorum etsi erat semper a me vehementer exspectatum, tamen vicit opinionem meam meque ita vel cepit vel incendit, ut cuperem quam celerrime res nostras monumentis commendari tuis; neque enim me solum commemoratio posteritatis ac spes quaedam immortalitatis rapit, sed etiam illa cupiditas, ut vel auctoritate testimonii tui vel indicio benevolentiae vel suavitate ingenii vivi perfruamur. neque tamen, haec cum scribebam, eram nescius, quantis oneribus premerere susceptarum rerum et iam institutarum; sed, quia videbam Italici belli et civilis historiam iam a te paene esse perfectam, dixeras autem mihi te reliquas res ordiri, deesse mihi nolui, quin te admonerem, ut cogitares, coniunctene malles cum reliquis rebus nostra contexere an, ut multi Graeci fecerunt, Callisthenes Phocicum bellum, Timaeus Pyrrhi, Polybius Numantinum, qui omnes a perpetuis suis historiis ea, quae dixi, bella separaverunt, tu quoque item civilem coniurationem ab hostilibus externisque bellis seiungeres. equidem ad nostram laudem non multum video interesse, sed ad properationem meam quiddam interest non te exspectare, dum ad locum venias, ac statim causam illam totam et tempus arripere, et simul, si uno in argumento unaque in persona mens tua tota versabitur, cerno iam animo, quanto omnia uberiora atque ornatiora futura sint. neque tamen ignoro, quam impudenter faciam qui primum tibi tantum oneris imponam (potest enim mihi denegare occupatio tua), deinde etiam ut ornes me postulem. quid si illa tibi non tanto opere videntur ornanda? sed tamen, qui semel verecundiae fines transierit, eum bene et naviter oportet esse impudentem. itaque te plane etiam atque etiam rogo, ut et ornes ea vehementius etiam, quam fortasse sentis, et in eo leges historiae negligas gratiamque illam, de qua suavissime quodam in prooemio scripsisti, a qua te flecti non magis potuisse demonstras quam Herculem Xenophontium illum a Voluptate, eam, si me tibi vehementius commendabit, ne aspernere amorique nostro plusculum etiam, quam concedet veritas, largiare.

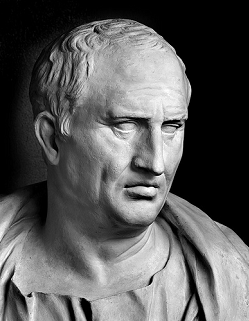

(Cicero, Ep. ad Fam. 22(=5.12).1-4)

Although I have more than once attempted to take up my present topic with you face to face, a sort of shyness, almost awkwardness, has held me back. Away from your presence, I shall set it out with less trepidation. A letter has no blushes. I have a burning desire, of a strength you will hardly credit but ought not, I think, to blame, that my name should gain lustre and celebrity through your works. You have often promised me, it is true, that you will comply with my wish; but I ask you to forgive my impatience. The quality of your literary performances, eagerly as I have always awaited them, has surpassed my expectation. I am captivated and enkindled. I want to see my achievements enshrined in your compositions with the minimum of delay. The thought that posterity will talk of me and the hope, one might say, of immortality hurries me on, but so too does the desire to enjoy in my lifetime the support of your weighty testimony, the evidence of your good will, and the charm of your literary talent. As I write these words, I am not unaware of the heavy burden weighing upon you of projects undertaken and already commenced. But seeing that you have almost finished your account of the Italian War and the Civil War, and remembering that you told me you were embarking on subsequent events, I feel I should be failing myself if I did not suggest two alternatives for your consideration. Would you prefer to weave my affairs along with those of the rest of the period into a single narrative, or might you not rather follow many Greek precedents, as Callisthenes with the Phocian War, Timaeus with the War of Pyrrhus, and Polybius with that of Numantia, all of whom detached their accounts of these particular wars from their continuous histories? Just so, you might deal with the domestic conspiracy apart from wars against external enemies. From my point of view there seems little to choose, so far as my credit is concerned. But there is my impatience to be considered; and here it does make a difference, if, instead of waiting until you reach the place, you immediately seize upon that entire subject and period. Furthermore, if your whole mind is directed upon a single theme and a single figure, I can already envisage the great gain in general richness and splendour. Not that I am unconscious of the effrontery of what I am about, first in laying such a burden upon you (pressure of work may refuse me), and secondly in asking you to write about me eulogistically. What if the record does not appear to you so eminently deserving of eulogy? But the bounds of delicacy once passed, it is best to be frankly and thoroughly brazen. Therefore I ask you again, not mincing my words, to write of this theme more enthusiastically than perhaps you feel. Waive the laws of history for this once. Do not scorn personal bias, if it urge you strongly in my favour—that sentiment of which you wrote very charmingly in one of your prefaces, declaring that you could no more be swayed thereby than Xenophon’s Hercules by Pleasure. Concede to the affection between us just a little more even than the truth will license. (tr. David Roy Shackleton-Bailey)